Fiery Fred and the damp squibs

Len Hutton, England's first professional captain, and his two Yorkshire team mate caused havoc in between the showers, recalls Christopher Sandford

Len Hutton, England's first professional captain, and his two Yorkshire team mate caused havoc in between the showers, recalls Christopher SandfordThere are a small number of cricketing snapshots which, apart from questions of nostalgia or period detail, have a lasting place amongst the icons of the game. England's Test series against India in 1952 may not have been the greatest, but it did include arguably the most photographed scoreboard in history: India 0 for 4 in the second innings at Headingley. By and large, England played with magnificent spirit and passed a significant landmark in appointing Len Hutton as their first regular professional captain.

In the event, 1952 would prove a major turning point. England went on to dominate international cricket for the next six years, winning eight series and drawing three, demoralising even the Aussies, home and away, in it the process. Stirring times. India, it has to be said, were badly handicapped by the injury or absence of experienced men like Vijay Merchant, Lala Amarnath and Mushtaq Ali. The great Vinoo Mankad, in the midst of a dispute with his home Board of Control, missed the first Test; when he reappeared for the second Test, he scored 72 and 184, took five wickets and fielded like a dog fresh off the leash. Vijay Hazare, meanwhile, a talented and often inspired cricketer, was widely regarded as a lacklustre captain. To compound India's problems, it rained throughout much of the summer.

That first Test at Headingley was a rout. Aircraftsman Fred Trueman, bowling up the hill for probably the last time in his long career, had figures of 3 for 89 and 4 for 27 on debut. A star was born. India scored a respectable first-innings 293 which included a stand of 222 between Hazare, who scored 89, and Vijay Manjrekar with 133. England replied with 334, and the tourists went in again on the Saturday afternoon.

Within a few minutes the match was all but over. They lost their first four wickets in the course of 14 balls, three of them to Trueman, without scoring a run. England astonished even themselves, the crowd fell silent, the bowling was not only electrifyingly fast but backed by tight fielding and sharp captaincy by Hutton. There were grounds for mild anxiety when India staged a tail-end revival, but it was too late. England won through on the fourth afternoon.

The second Test was one of pomp and some circumstance. A dramatic comeback, thrilling batting and the Queen's first visit as sovereign to Lord's; even the weather cooperated. Mankad immediately showed what India had missed at Leeds by scoring 72 of the tourists' first-innings 235, then bowling doggedly throughout the England reply - a small matter of 537. Hutton made a typically efficient, chanceless 150.

Much later that same Friday, Godfrey Evans, never one to stint himself while in London, enjoyed the convivial hospitality of a nightclub off Regent Street. The eventual result was that England's wicketkeeper went out to bat on Saturday morning, a wicket having fallen on the last ball of the previous day, nursing a hangover of, as he later admitted, `gale-force dimension'. Two hours later, Evans was on 98 not out. His partner Tom Graveney remembers that he was happy to "stand back and watch... Godfrey was so brilliant and so unorthodox, there were moments when I was laughing out loud". At exactly 1.28pm Evans was ready to face what he assumed would be the last over before lunch. Hazare set his field as if in slow motion. The Indians had been run ragged for two hours and they looked it. Finally Hazare reached his mark. He turned, and at that moment the umpire, Frank Chester, raised his artificial arm, snatched off the bails and announced, "Time gentlemen, please". Evans had been denied by two runs the opportunity to become the first Englishman to score a century before lunch in a Test.

At 59 for 2, it seemed India were doomed to lose by an innings. But Mankad, save for one sharp chance he offered first slip, went placidly on. His 184 was a record for an Indian Test player. Beginning warily, playing forward with bat almost exaggeratedly straight, he relished the quick single from a defensive prod. But Mankad also enlivened proceedings with more and more violent onslaughts against the spinners. He batted like a sports car being run in.

Immediately after the Queen's visit on the fourth afternoon, he swung over a half-volley and was bowled by Jim Laker. India finished 76 ahead and, after a false start by Reg Simpson, England duly won on the final morning. Probably no one expected India to pull back from 2-0 down but after Lord's things seemed to disintegrate. The tourists were outclassed but still unlucky at Old Trafford, where they undoubtedly had the worst of conditions. Play was first delayed and then constantly interrupted by rain and bad light on the first day; Hutton again mingled defence and offence perfectly, and Peter May was at his thoroughbred best, but it was hard going for players and spectators alike. Given that rain fell throughout - enough to take 50 runs off the pace of the outfield, Evans believed - a total of 347 was eminently respectable.

Once again, it then became Trueman's day. Bowling with a gale at his back and supported by electric fielding, he was simply too good. The Indians could scarcely pick up their bats before Trueman's pace went through them. At one stage his field consisted of three slips, three gullies, a short mid-off, and two short legs. Evans, Tony Lock and Graveney all pocketed sharp catches, and India slumped to 58 all out, their lowest Test score at the time, and Trueman returned figures of 8 for 31, his best in Tests.

It seemed the tourists could not have become any more demoralised, yet matters worsened. In an extraordinary sequel they collapsed completely for the second time, Alec Bedser taking 5 for 27, and England won at a trot. It was the first time that a side had been dismissed twice in a day.

At this stage, Hutton's record as captain was unblemished. He had scored centuries at Lord's and Manchester, used his bowlers shrewdly and even charmed the Press with a mixture of modesty and dry wit. It was hard to see what more he could do, short of staying behind to sweep the pavilion afterwards. Yet doubts remained. A number of selectors and cricket writers like E.W. Swanton worried that "there were limitations in Len's appreciation of the broader scene". Indeed there were mutterings throughout the 1952 season about recalling one of the "officer class', like Freddie Brown, for whom taking an interest in other people seemed to be less of an obvious effort. Hutton himself would tell me shortly before his death in 1990 that "my face never fitted". Just nine months after crushing India he would be reappointed England captain by a single vote.

The weather again dominated proceedings in the fourth Test at The Oval, where there was no play at all on the third and fifth days. Even when the teams did take the field, sawdust had to be used liberally on the run-ups and towels were constantly brought out to wipe the ball. Both sides turned a blind eye to victory.

England won the toss, batted and eked out 326 for 6 declared, amidst frequent interruptions for rain and bad light, of which David Sheppard made 119. The tourists, in turn, knew what to expect from Trueman and Bedser, and within 30 minutes their worst fears were confirmed. In a dramatic first seven overs, half the Indian wickets fell for six runs. Hutton's field placing at Old Trafford would seem hopelessly laid-back by comparison: when Trueman roared in for the kill he did so to an arc of live slips, two gullies and two short legs. India collapsed to 98 all out, giving them an aggregate of 238 from three consecutive, completed Test innings.

England had a wonderful chance to make it a 4-0 series win, and lost it in circumstances depressingly familiar that summer. With the ground waterlogged on the final morning, the match was abandoned as a draw. Hutton, Graveney and, more surprisingly, Evans were the leading England batsmen in the averages; Bedser and Trueman did the damage with the ball.

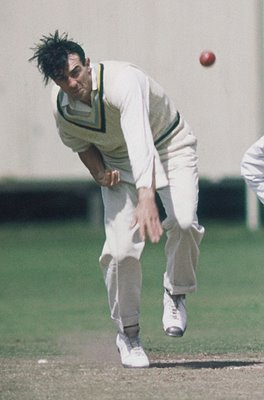

Trueman was the find of the summer. Long before he came near the wicket you could tell that something extraordinary was going to happen. The black curly forelock, the swing of his broad shoulders and the general air of self-confidence all signified that this was no run-of-the-mill trundler. Only at Lord's did the Indians look vaguely comfortable against him, and even there Tnteman took eight wickets in the match.

A golden future loomed. In 1952, Tony Lock also began his long and colourful Test career. There was Freddie Brown letting it be known that a young tearaway at Northampton would "win the Ashes for us", the prodigy in question being Frank Tyson. Brian Statham, already noticed by England, cheerfully wheeled away at Old Trafford. Ken Barrington was perfecting his technique in the nets at The Oval. And there was talk of an Oxford freshman called Cowdrey.

This article first appeared in the September 2003 edition of The Cricketer.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home